|

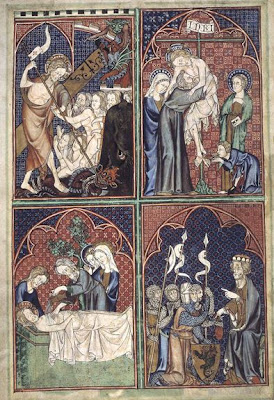

A couple of weeks ago the lovely people over at Battle Castle held a medieval soup challenge! Writer Nicole Tomlinson was inspired to begin the challenge after a visit to Poland's Malbork Castle where she saw the above picture of Cherry Soup in the book The Cuisine of the Teutonic Grand Masters in Malbork Castle written by the chef there Bodgan Galzaka. You can read more about this at the blog here.

The challenge was to create the recipes using ingredients available to you but would also likely have been available to the Teutonic Order. Whilst it is too late to join in Battle Castle's soup challenge (apologies for my lateness in writing this!) you could still have a go at creating some of the delicious looking medieval soups that were inspired by the Teutonic Knights. Battle Castle have released three recipes for you to try out for yourself:

|

| Mushroom Soup |

|

| Lentil Soup |

|

| Cherry Soup |

“ZUPA WISNIOWA” - Cherry Soup

Described as “a warm winter sangria”, this enchanting recipe captures Chef Galazka’s colourful vision and enahnces sweet fruit flavours to balance the delicious dryness of the #1 ingredient - red wine.

Ingredients:

2 398 mL cans Bing cherries, 500 mL water, 100 mL wildberry honey, 1 L dry red wine, 250 mL Greek yogurt, 1 peach, 3 leaves of fresh mint, 1 lemon, ground cinnamon. Makes 6 meal-sized servings or 10 appetizer-sized servings.

Preparation:

Drain cherries. Pour water and honey into a pot. Add half the cherries and cook for 15 minutes at medium heat. Cut peach into thin slices, grate lemon zest and chop mint. Add wine to the pot and cook until alcohol has evaporated (approx. 3 minutes). Add cinnamon bit by bit, tasting until a desirable level of warm spiciness is achieved. Portion other half of cherries into bowls and then ladle hot soup over them. Add a dollop of Greek yogurt to each bowl. Finish with peach slices, mint, and lemon zest. Serve promptly.

Recipe inspired by “The Cuisine of the Teutonic Grand Masters in Malbork Castle” by Bogdan Galazka, Head Chef at the Gothic Cafe, located at the castle. Malbork is one of six castles featured in the Battle Castle action documentary series, airing in Canada in early 2012 on History Television and on Discovery UK.